Biking The Forgotten Canal Du Midi: Day 4

While the canal has endured, it has faced problems from the very start.

Read the previous chapters in this series: Day 1, Day 2, Day 3

From Homps, the next stage would take us 31 miles to the village of Villeneuve-lès-Béziers. We were propelled by the adrenaline of having passed the mid-point and the knowledge that by the next day we would be celebrating the end.

This stretch of the canal is more arid and treeless, surrounded by farmland and rolling hills that ran south to the Pyrénées, reminding us of a long-ago trip to Tuscany. From Homps, the canal serpentines in large loops to the south and then to the north. We decided to shave off time by cutting across local roads which would shorten the trip by several miles.

This made for smooth, peaceful riding along country roads that took us along the northern edge of the Corbières wine region, one of our favorites. I can’t remember having a bad wine from Corbières, which extends from Carcassonne to the Mediterranean coast and south to the Pyrénées foothills. The region produces primarily red wines that are hearty, sometimes a touch spicy, and extremely reliable. Vineyards surrounded us as far as we could see in each direction and the temptation to make a detour toward a wine domaine for a little tasting tugged at us (less so for the kids), though we decided ultimately it could easily derail our day.

While this all felt remarkably peaceful to us, the reality for those who live and work along this stretch is much more troubled.

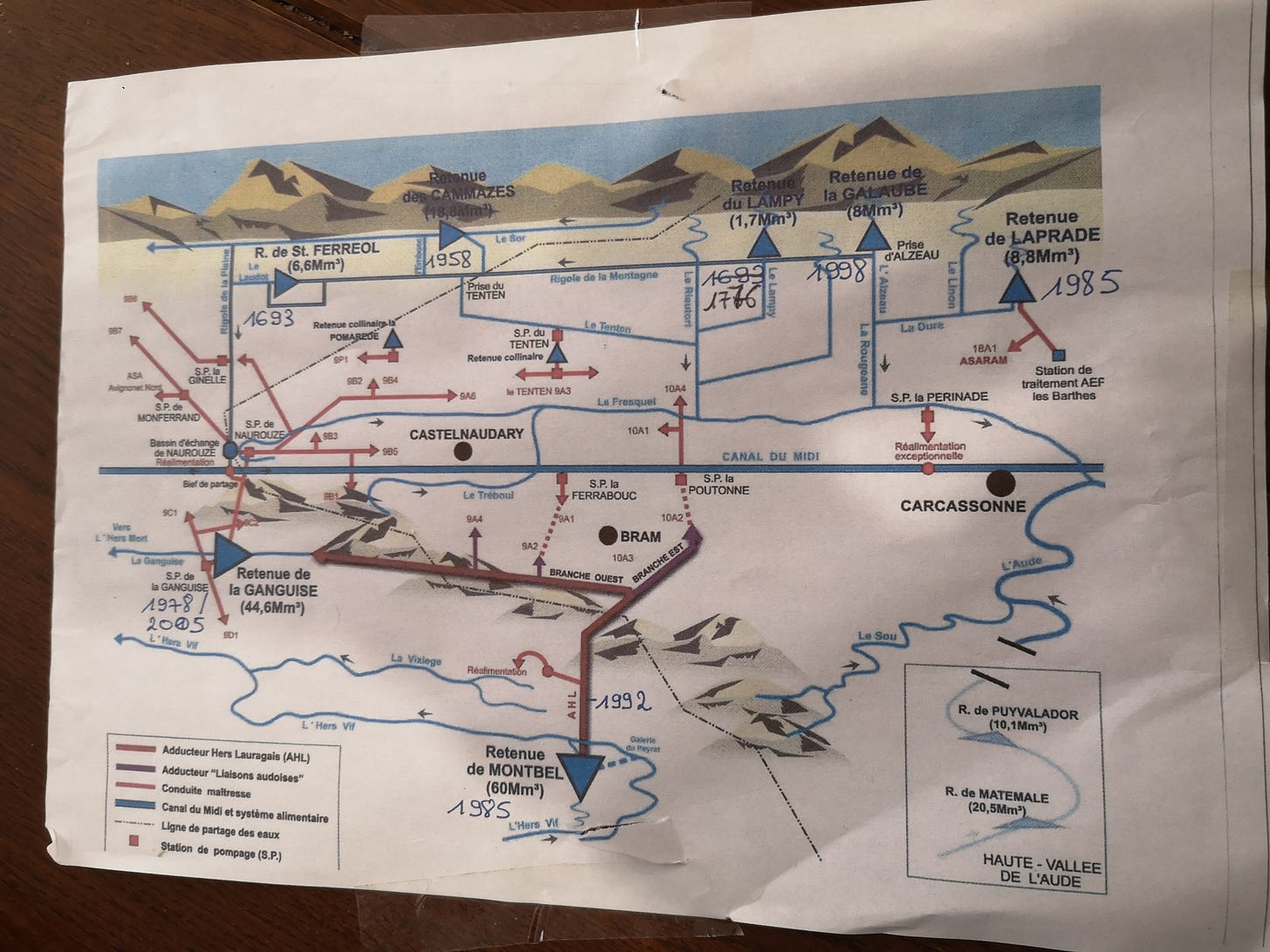

This agricultural region has an increasingly tense relationship with the canal thanks to concerns over the water supply driven by the impact of climate change and population growth. The canal is part of a wider water network that stretches to the north and the south. Many farmers in the region from Carcassonne to the Mediterranean depend on the canal for irrigation, and they are increasingly worried that there’s not going to be enough for everyone. The canal uses 41% of this system’s water supply, with 18% going to farmers and 41% going to a rapidly growing number of residential and commercial users.

The water supplied to irrigate farmland and small towns is provided by two companies: BRL and L’Institution des Eaux de la Montagne Noire (L’IEMN). Their hydraulic systems pump water out of the canal and toward the farms that are dependent on it. For decades, Serge Vialette of Castelnaudary was one of those farmers until he retired in June 2016 and officially passed his farm on to his son.

During a visit to his farm long after our ride, the short, stocky 4th generation farmer with glasses and a gray, bushy mustache greeted me with a broad smile and a strong handshake. Vialette is a big name in this region, having been president of both a national and regional farming union. He is also renowned as a founder of Castelnaudary’s annual Cassoulet Festival.

I had come to talk to him because the many hats he has worn included being president of the local irrigation cooperative that manages the water received by farmers from BRL.

Vialette grows corn, wheat, sunflowers, and grapes on his 300-acre farm just north of town, with about half of that being irrigated. Like many in France’s increasingly strained agricultural sector, he has struggled to remain profitable as subsidies have shrunk and costs for items like water have risen. His frustration is targeted at regional leaders who he argues had previously failed to invest sufficiently to expand this system in a region that has been adding 50,000 new residents annually in recent years.

He’s irritated that proposals to build new reservoirs have been opposed by environmentalists while farmers are under increasing pressure to find ways to reduce water usage by changing crop management techniques. As more farmers leave land fallow or quit altogether, Vialette said the strategy that has saved his farm is crop diversification, something only possible for farms connected to the irrigation system and able to afford enough water.

With two mountain ranges in the region, including the Massif Centrale, he regrets that so much water running off these peaks is simply spilling into the sea rather than being used to help farmers, residents, and the canal.

“The only thing that can produce a profitable farm is diversification by way of irrigation,” he said. “For us, the water is the priority. Today, France is capable of retaining these two huge fountains on each side of the region. It’s completely irrational, this debate. It is necessary, to reinvest in the reservoirs and stockpile the rainwater, for the population, for the tourism economy, and the agriculture economy.”

Troubled Waters

The canal’s water problems stretch back to its earliest days.

Just five years after its inauguration, the king’s chief military engineer Sébastien Le Prestre de Vauban came to inspect it and was deeply displeased. The water supply was so unreliable that there was even some talk of abandoning the canal. Instead, Vauban ordered the construction of another trench to funnel more runoff from the nearby mountain into Riquet’s Saint Ferréol reservoir, with its damn also being built higher. Over time, two more dams were built further up the Black Mountain, creating the Lampy and Galaube reservoirs.