Despite a raging pandemic, various personal and professional obligations required me to make the 7-hour drive between Toulouse and Paris several times this past summer. In a country full of spectacular vistas, the route along A20 to A71 to A10 that cuts through the heart of central France does not offer much in the way of dramatic scenery. While there are some verdant patches and some interesting detours from the highway, mostly this drive is a grind spent counting the rest stops and trying not to stare at the odometer to calculate how much longer to go.

So during one of the return trips south from Paris, I decided to take the tiniest of vacations by pulling off the highway and walking around Orléans for a couple of hours. I can’t exactly say why I chose this detour, other than the fact that the name Orléans looms so large in French history, particularly for the whole Joan of Arc thing.

About 90 minutes from Paris, I navigated a morass of road construction in an attempt to reach the Orléans city center. This is always the problem with such improvised pit stops. It’s never as easy as one thinks to actually reach a destination that involves lots of local roads and stoplights and one-way streets. There is a reason, after all, that rest stops were invented to seduce us with their convenience while we ignore their blandness.

Orléans sits along the Loire, which is France’s longest river, a fact I have engraved into my head after months of studying for our French naturalization appointment earlier this year. While locals will no doubt regale you with the many interesting historical moments witnessed in a city that traces its history back thousands of years, Orléans is best known for being saved by Joan of Arc in 1429 from the English during the 100 Years War. While Jeanne d’Arc met a famously fiery end, she has been immortalized across the country in the form of countless statues and street names. (And that song by The Smiths.)

The thing I’ve learned after 6 years of living in France is that there is no footnote of history too small or cultural event too insignificant that the massive French tourism machine won’t try to turn it into an attraction of some kind to lure economically critical visitors. But in the case of Joan, she is a legit icon. So it’s no surprise that Orléans’ tourism pitch revolves around her.

The Orléans Office of Tourism offered a staggering selection of Joan memorabilia and several tours. I am a lover of kitsch and so was tempted by several baubles. One of my favorite items owned by my wife when we first started dating was a Ché Guevara hot plate that is long since departed, alas. Still, while I might have found these Joan items amusing, I knew the kids would just roll their eyes and so I resisted the urge.

My knowledge of Joan’s story is limited to broad strokes. Though earlier this year I did try to watch Jeanne, a movie by director Bruno Dumont (apparently his second on the teenage martyr). The film had been accepted into the Cannes Film Festival suggesting it had some merit, but I gave up after the first 30 minutes which consisted mainly of Joan standing in some sand dunes discussing battles that occurred offscreen and then staring for long stretches into a mystical void. I could have used a dash more Braveheart-like battles.

Orléans On Foot

After driving around the city center, I pulled into a parking garage. And, of course, upon emerging from this automotive underworld, the first site was a statue of Joan looking a bit weathered but still keeping vigil over the city.

The statue is located in Place du Matroi, which is a classic French plaza surrounded by enticing terraces full of people enjoying an afternoon coffee and staring at the obligatory carousel. I have still not learned why these are ubiquitous in French cities. I’m sure there’s an interesting tale behind the carousel arms race or perhaps the cunning mafia-like organization that builds and operates them, but I haven’t heard it yet.

The buildings surrounding the plaza are made from the white stone that the French went gaga for in the 19th century, which is beautiful in limited amounts but can also create a kind of sameness to many French cities. Of course, millions of tourists dig that look, and I get that, and Instagram thanks them for it.

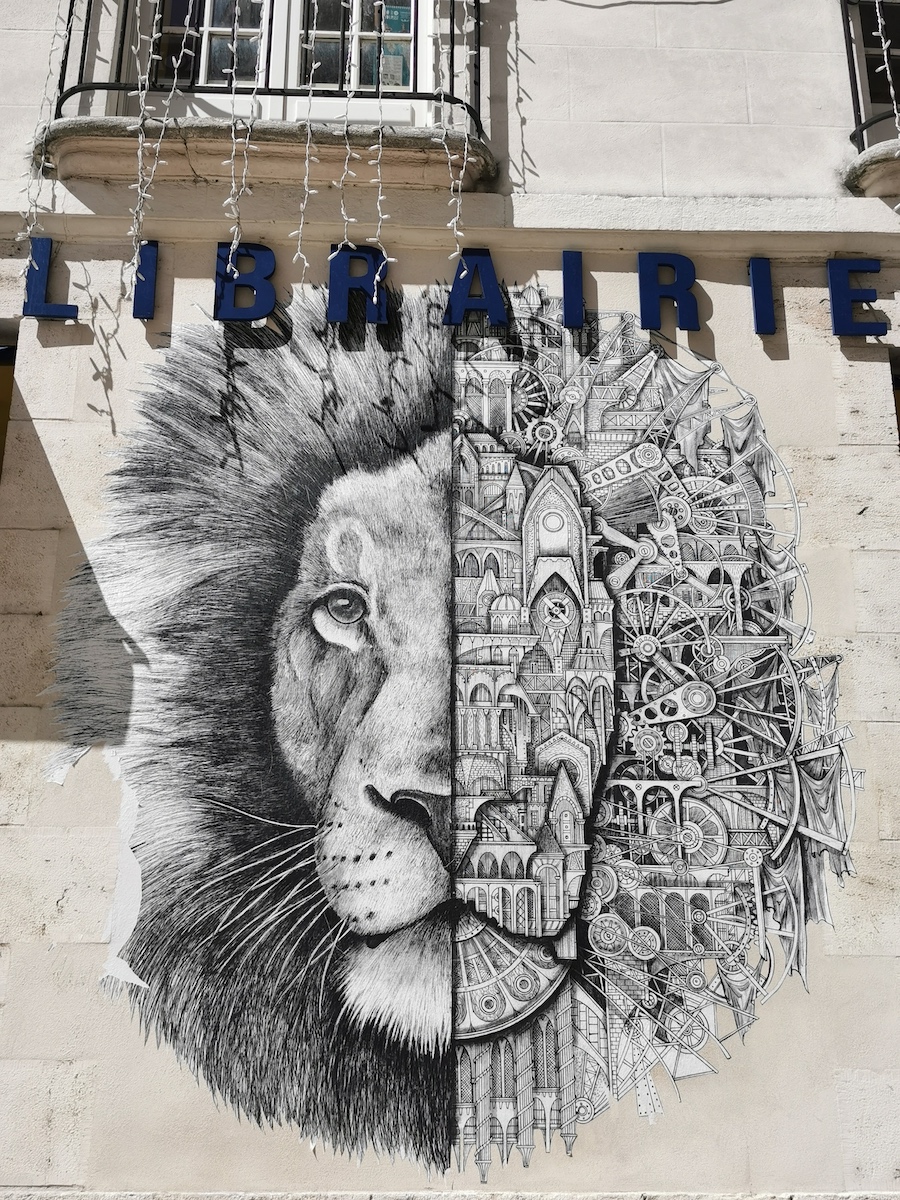

Fortunately, walking south off the plaza, the city displayed a bit more personality. Turning just southeast off the plaza I crossed paths with this dazzling bit of street art.

And a few doors down, these more colorful relics from a Medieval period had somehow managed to survive the wrecking ball that made way for all that white stone. Their colorful wooden beams reminded me a bit of our visit to Honfleur in Normandy.

Hôtel Groslot

More impressive to my eye was the Hôtel Groslot. You can’t see it too well in this photo, but just in front of the stairs, there is a bronze picture of JoA standing guard. I loved the multi-hued brick arranged in diamond patterns, an impressive and painstaking bit of craftsmanship that creates a mesmerizing effect. It recalled some of the Flemish-tinged buildings in Lille, though having no expertise in architecture that observation is based on absolutely nothing at all. Purists will likely recoil at the reference.

The Groslot name comes from the Protestant family who lived there when it was built in the 16th century. It was the scene of a pivotal moment in France’s history when the teenage Catholic King François II came amid religious tensions with the upstart Protestants and then died there in 1560. This occurred just before the outbreak of the Wars of Religion that lasted for several decades. François’ 10-year-old brother became King Charles IX. And Frank’s wife, Mary, fled the country to Scotland where she met a memorable end as Mary Queen of Scots.

On a more purely juvenile note, I found myself chuckling at the name “Groslot” because “gros lot” in French means “jackpot.” It probably isn’t pronounced the same, but honestly, I was too lazy and embarrassed to ask.

Cathédrale Sainte-Croix d’Orléans

If France’s white-stone fetish is a bit fatiguing, I remain an absolute sucker for its cathedrals. In this city, that means a visit to Cathédrale Sainte-Croix d’Orléans.

A Gothic church initially opened in the 14th century, it’s naturally associated with Joan who made a stop here for mass in 1429 while defending the city from the English marauders. The church she visited was all but leveled by Protestants during those Wars of Religion in the late 16th century.

Rebuilding began in the early 1600s and dragged on to the 19th century. The re-opening was timed with the 400th anniversary of Joan’s victory and the restored edifice contains many tributes to her. That includes the 11 stained-glass windows that tell the story of her life.

Perhaps it is the lapsed Catholic in me, but I still find structures like this one immensely uplifting, despite the obviously awkward political-economic-social-religious issues they raise. I guess those conflicted feelings are not so out of place in a country that still officially celebrates so intensely a religious martyr and saint as a political and military hero and recognizes so many Catholic rituals as national holidays but also holds firm to laïcité.

After exiting the church, I walked back to the parking garage (following Rue Jeanne d’Arc naturally!) and continued the slog back to Toulouse. I’m sure Orléans warrants a longer visit one day and no doubt its partisans can furnish a long list of must-sees and must-dos and must-eats. But for a quick spin, this first glimpse of Orléans still managed to be a rich and satisfying entrée.