My first experience doing any type of foreign correspondent work began on this day 6 years ago and under the grimmest of circumstances. Our family had moved to France five months earlier from California, and I had quit my job at the Los Angeles Times. Landing in France without much of a professional plan or any personal connections, I continued to do some freelance work for the Times that fall, writing mostly features.

The shooting at Charlie Hebdo on January 7, 2015, represented something else entirely. As a newcomer to France, I’d never heard of Charlie Hebdo, and during the day, struggled to grasp the significance of the publication while watching the coverage from our apartment in Toulouse. I then received a late-night call from a Times editor asking me if I could go to Paris the next day. Of course, I said yes.

I had covered various breaking news stories over 2 decades in journalism that required me to parachute into unknown places. But of course, these were all in the United States. Landing in Paris the next morning was something else entirely. At that point, after 4 months of Duolingo, I didn’t really speak much French. And perhaps even worse, I had only been to Paris twice, and both visits had been…miserable.

The first occasion was a Eurorail adventure I was taking in the summer of 1992 with my girlfriend at the time. We were on an overnight train from Amsterdam to Barcelona that required a late-night change at one of the Paris train stations. With a couple of hours to kill in between, and somehow a few Francs in our pocket, we risked it all by stepping out of the station in search of some bottled water. I spotted a restaurant with a well-lit refrigerator selling water, entered, reached for a bottle, and then watched the sweaty container slip through my hands and explode on the floor. A furious woman charged at us from behind the bar, screaming and pointing her finger, and just generally freaking us out. Terrified, I pushed all of our Francs at her and rushed back out. This was the sum total of my encounter with an actual French person for the first 22 years of my life, and it was enough to confirm every stereotype I’d ever heard. Hate Americans. Don’t speak English. Rude. Check. Check. Check. My nativist self was never going back there again, I promised myself.

The second time I visited Paris came 22 years after the great exploding water bottle debacle and only served to deepen my antipathy toward a city that every other human on the planet loved unconditionally. It was early December 2014 and I had been invited to attend Le Web, a tech conference that had been influential for many years but was now about to draw its last breath. Unfortunately, Paris in early December turned out to be an intolerable combination of freezing rain, early sunsets that created a sensation of perpetual darkness, and frustrated mobs of people elbowing their way along the sidewalk.

Admittedly, I also made a series of rookie errors when planning this trip. The conference was being held at Les Docks, a venue just north of the périphérique, the highway that encircles Paris like a sphincter muscle. Everything outside this demarcation feels so different and distant from what one actually thinks of as Paris that it might as well be in London. Not knowing this, I booked an Airbnb to the north of Les Docks after carefully consulting Google Maps which led me to believe that it didn’t seem far from the venue. It was far. In the age of Google Maps and smartphones, it amazes me that I’m still able to so often misjudge geography by such a large margin. It turned out I was staying in the town of Saint-Denis, outside of the City of Lights. When I met my host, I told him this was my first visit to Paris in many years. “Ah,” he said. “But here, you are not in Paris. You are in Saint-Denis.” The countless time I spent trudging through dodgy neighborhoods at night and in the early mornings would drive home this distinction in the coming days.

So landing in Paris a third time, I had no idea where to begin. I met up with another Times freelancer from London who attempted to give me some tips. Then I needed to find a translator, book a hotel, figure out the entire French legal bureaucracy, and, actually do some reporting. I had started my career as a cop reporter, but of course, all my intimate knowledge of local police departments in North Carolina was completely useless in Paris. By the time I met my translator, it was 4 p.m. The Times wanted a profile of the brothers that same day. We went to get a burrito.

Paris, ça va

I spent the next 24 hours flailing like a fish trying to avoid being pulled over a waterfall into the abyss below. The ambiance of nationwide grieving, coupled with the ceaseless freezing rain did not really allow me to discover the reputed charms of Paris. I bought 3 umbrellas the first day and watched each of them be mangled by gusts of wind before finally just giving up.

The next morning at the hotel and wondered if I shouldn’t just head back to Toulouse and stop wasting everyone’s money. Instead, I woke up to the news that the shooters had been cornered in a suburban town northeast of Paris after a manhunt through the previous night. The problem was that all the Times editors were safely asleep, and so I had to make the call on my own whether to try and get out there to report from the scene.

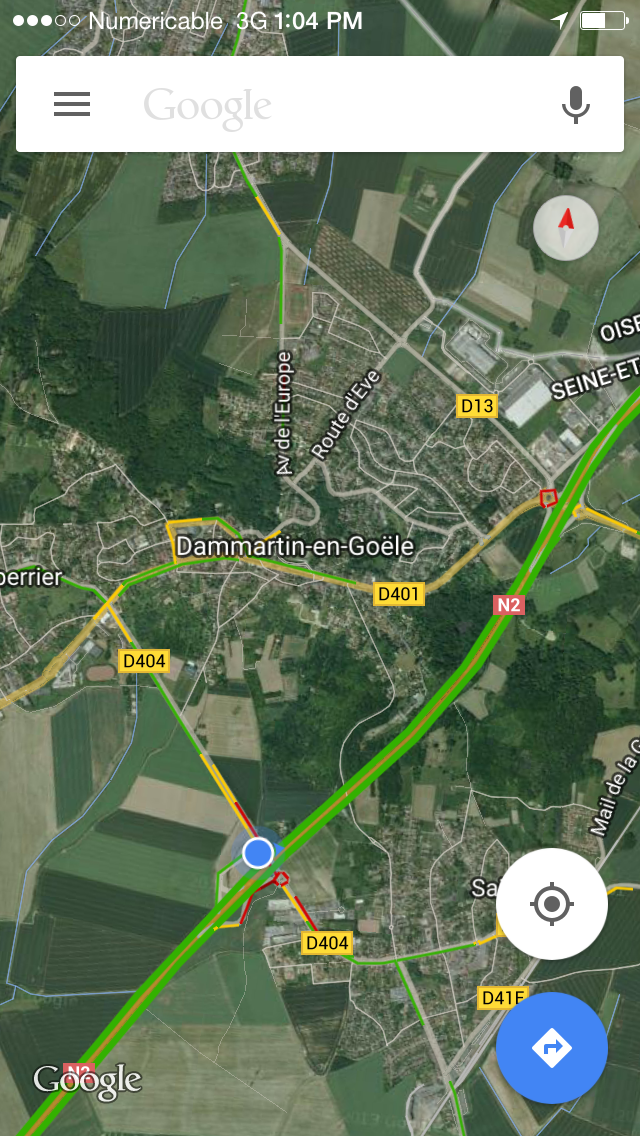

Of course, I had no car and no idea how any of the local transportation options worked. Sitting in the lobby, I Googled like a fiend. I must have looked as completely overwhelmed as I felt because, at just that moment, a Swedish journalist approached me and asked if I was covering the Charlie Hebdo story. I said yes, and then he asked if I wanted to ride with their team out to Dammartin-en-Goële. Trying not to weep in gratitude, I said yes, grabbed my backpack, and hopped into their van.

Thirty minutes later, I got my next lesson in the glamorous life of a foreign correspondent. The brothers had been cornered in a printing shop, where they had taken a hostage. The police had barricaded the entire town, which was on a strict lockdown. So we were forced to park near an exit ramp outside of town along with about 1,000 other journalists.

We waited for about 6 hours, mostly sitting in the van to avoid the cold and damp conditions. I can remember doing a short interview by phone with NPR, pretending to be actually someone who knew what was going on. And I briefly left the van to make my first and only visit to a McDonald’s in France, because it was the only restaurant in proximity.

Late in the afternoon, the brothers were killed in a shootout with police, who subsequently declared it safe to enter the city. I rode with my Swedish comrades to a command center the police had set up in the city center. And after a short press conference at which I understood virtually nothing, I then went in search of local residents to interview about their day of terror.

My first Galette Des Rois

Amid all the confusion and the rush to get out to the scene, I hadn’t had time to re-connect with the translator. So I wandered the streets of this small suburban town on my own. Such assignments were never my favorite, even in English. I dreaded the moments when an editor would demand, “Go to the mall and interview some random people about this weird weather we’re having.” Approaching such strangers to elicit responses could take me forever.

As I knocked on doors, I stumbled through some rehearsed phrases. Understandably, most people refused to open their door. The few that did said they did not want to be interviewed. After 2 hours of futility, I was about to give up and walk back to the command center.

Making one last attempt, by total luck the door was opened by a youngish father who spoke near-perfect English. He invited me in. And over the next couple of hours, I learned something about the French that one doesn’t tend to hear amid all the clichés about them being cold to foreigners and disdainful to those who don’t speak French. If you get past that exterior, the French are intensely social and offer a culture of warmth and hospitality that exceeds even what I experienced living in the American South for more than a decade.

The husband introduced me to his wife, and two young children. It had indeed been a scary day as the parents received word that the kids had been placed in lockdown at their schools. Information was scarce. Nobody knew how real the danger was.

As they recounted their day, they asked me if I’d eaten. Would I like some dinner? Perhaps some wine. I hesitated, journalism ethics and all. But after my second day of misery, and having still only eaten one meal from McDonald’s, I relented. As we ate a kind of improvised meal standing around the kitchen counter, the parents began sending messages via a WhatsApp group for families at their kids’ school to find other people who might be willing to tell me their stories.

Not long after the meal, it came. The mother opened a cardboard box and slid out the galette des rois. I demurred and said I didn’t really have time for dessert. But, they said, this is not dessert. This is Galette des Rois! It’s a tradition and I simply must.

They proceeded to explain the Festival of Epiphany (L’Épiphanie) to me. Despite being raised Catholic and even having been an altar boy, I had never heard of this festival. Though, of course, I knew about the Three Wiseman and all that. But there was cake? We never had cake to mark this day growing up. As they sliced the plates, the kids distributed them while the parents explained that inside one of the pieces there was a small fève, a trinket of some kind. Whoever got the fève was king for a day and got to wear the paper crown that came with the galette.

I did not get the fève. I was frankly relieved because as I understood it, that would mean I’d be obligated to buy the next cake. Despite having just met these people, somehow I was beginning to feel like an adjunct member of their family. And I was really beginning to wonder if they would expect me to come back the next day with another galette.

Leaving was not easy. “Some coffee?” they offered. No, no, I really must get going. I had a story to write and I didn’t want to miss my Swedish connection back to Paris. I said my goodbyes, which took another 10 minutes. And then walked back to the command center. Naturally, the spokesman for the police was serving coffee to all of the reporters. I don’t recall any police spokespeople in North Carolina ever serving me coffee.

Back at the hotel an hour later, I wrote furiously, trying to capture the drama of the standoff and the reactions of the local residents. I filed my story at about 2 a.m. One of the joys of freelancing for a West Coast newspaper is that their final deadlines are about 3 a.m. or 4 a.m. Paris time.

Groggy the next day, I learned the next hard lesson about foreign correspondent life. Almost nothing I wrote was published. In the midst of the standoff with police in the suburbs, another tragic drama had unfolded in Paris when a terrorist took hostages at the Hyper Cacher market. Four people were killed at the Jewish market, plus the terrorist. The wave of grief had deepened.

I stayed two more days in Paris where the mood had gradually shifted to one of defiance. On that Sunday, 4 days after the Charlie Hebdo shooting, the city held a massive march that demonstrated a remarkable sense of unity. It was a breathtaking moment to be in the middle of this sea of people. Paris was kind enough to (mostly) stop the rain that day. I even managed to get a byline.

This was the beginning of my rapprochement with Paris. But I still think of that galette as perhaps the real turning point, a small glimpse into the warmth of the French people, and the beginning of my strong affection for France’s culture.